By | Published Aug 28, 2019 @ NLGJA CONNECT: Student Training Project

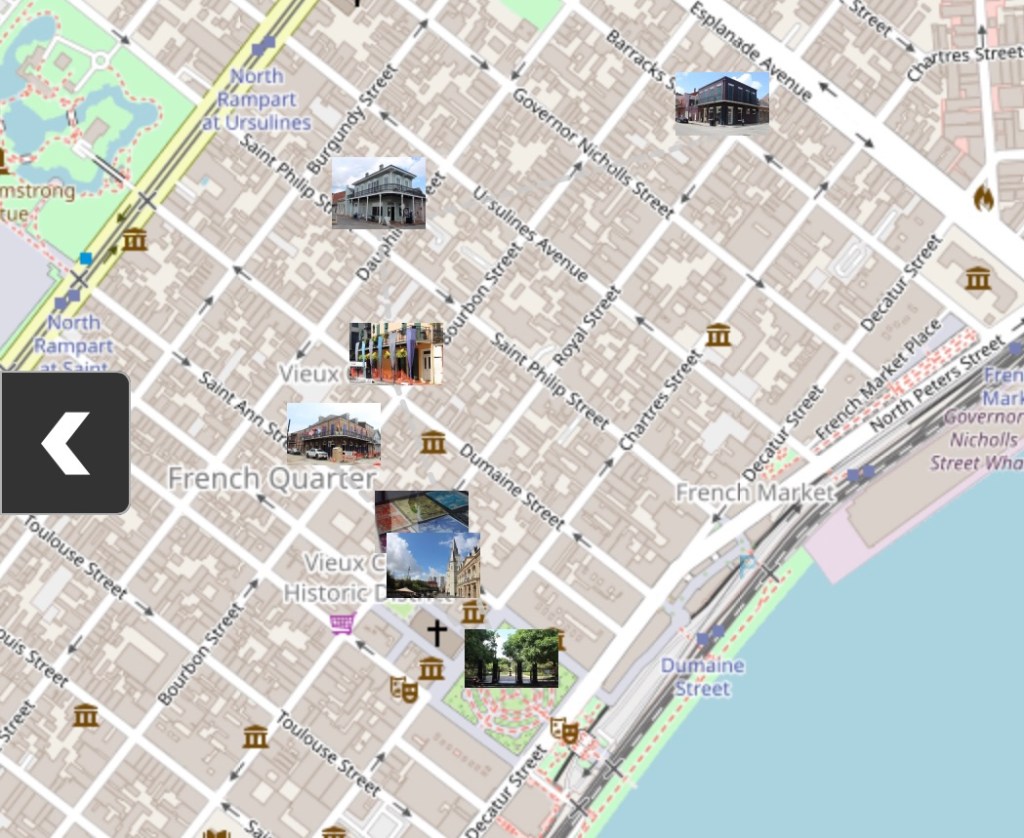

Jackson Square Park was once a meeting stop for the oldest queer protest in New Orleans. (Photo by Ethan Knox)

Jackson Square Park was once a meeting stop for the oldest queer protest in New Orleans. (Photo by Ethan Knox)

A royal entourage, adorned with elegant and extravagant furs and colors crossing the rainbow, followed haphazardly behind Louis XIV as he marched steadily down the street. Behind them, a few thousand subjects of this kingdom moved in beat to music, their rhythms and motion matching the energy as they bellowed, hollered, danced and generally celebrated.But something about this Louis seemed strange. Perhaps it was the oppressive heat (though that was mitigated by secret ice packs sewn into every inch of the elaborate costumes). Or perhaps what stood out above all is that rather than France, these crews paraded down the French Quarter of New Orleans during Labor Day weekend, and Louis’ real name was Frank Perez, a local tour guide, archivist and one of the Grand Marshals of last year’s Southern Decadence.

Southern Decadence, an annual festival now in its 48th iteration, draws queer people to New Orleans every summer for days of festivities. It is expected to break attendance records once again this year.

The 47th Southern Decadence, led in part by Perez, attracted 250,000 tourists to the city, and contributed more than $275 million dollars to the local economy, according to the festival’s official website.

While there are no official criteria to be Grand Marshal, for Perez, who was responsible for choosing his own successor, there are some qualities those people should have.

“You’ve got to be local. You’ve got to be someone who’s generally alcoholic, somebody who might pass out in the gutter, fuck anything that moves, do a lot of drugs—then you’re a candidate.”

The event itself began in 1972 when a group of college-age friends who called themselves the Southern Decadents threw a going-away party for one of their members. That first summer, only about 50 people showed up, but the fête was such a success that they decided to do it again. By year three, the event had begun to take on a life of its own. A crude version of a parade started at Matessa’s Bar, where the friends decided to begin with a pub-crawl before making their way home. That year, the decision was made to appoint a Grand Marshal. Soon, choosing themes, color schemes, songs—and a successor—became part of the marshal’s job description. These traditions live on today.

After many members of the original group passed away, the disorganized and chaotic parade changed yet again. Matessa’s Bar shut down, and a new generation took control. The parade now begins its route at another gay bar, The Golden Lantern. Decadence has expanded so wildly that thousands of dollars are now required to finance it. Official events, such as drag shows and fundraisers, pepper the whole month of August, leading up to the main event.

In some ways, however, the original spirit of decadence remains. Southern Decadence has traditionally accepted money from sex-focused organizations: bars, a casino, and companies that sell condoms and poppers.

“Our philosophy is to only accept sponsorships and corporate money from corporations and businesses that promote general depravity and decadence,” said Perez, who is often involved with Decadence events, though his participation this year remains minimal due to his other obligations as a full-time tour guide and the president of the LGBT+ Archives Project. “If your corporation or your business promotes human vice, we’ll take your money. Otherwise, no, because this is not Pride. There’s no political agenda to decadence; this is hedonism, this is pleasure for pleasure’s sake.”

Though some participants feel uneasy about the influx of corporate money for the event, many straight-owned businesses see the increased revenue as a chance to earn some rainbow dollars.

Jeffery Palmquist, one of four Grand Marshals in 2016, said the elevation of the celebration to a place where heterosexual establishments can also engage a queer community is a good thing.

“It’s always fun to see the gay-friendly French Quarter become really gay during Southern Decadence. A few rainbow flags turn into one, and sometimes many, on almost every business,” Palmquist said in a text message. “The gay community welcomes the influx of people coming to celebrate, and the money is much welcomed after the slow summer months. Leading up to Decadence weekend has now become a fun buildup, with raising money to produce the parade and the chosen charity of the year.”

Kristian Sonnier, the vice president of communications and public relations for New Orleans & Company, the city’s tourism board, said in a statement that Southern Decadence is an important part of the city’s culture.

“New Orleans has a 300-year history of inclusion and diversity, so it’s no surprise that Southern Decadence in New Orleans has grown over the past 47 years to become a major summertime event that draws people from around the region and country,” Sonnier said. “The residents of New Orleans are well known for their joie de vivre and passion for special events. Southern Decadence is one more beloved occasion, among many others, where that passion is on display for all the world to see and attend.”

As the Southern Decadence parade requires more money to operate and the festival raises more cash, some participants feel that queer voices are being erased. And others worry that the festival lacks inclusion for queer people of color, trans people and women. Even historians of Southern Decadence like Perez concede that the celebration is very cis-gendered and aimed toward white gay men.

A local DJ, known as Jenna Jordan, hoped to combat this exclusion by beginning GrrlSpot, a pop-up lesbian bar and dance party, in 2005. The program, much like Decadence, has started to expand, and now welcomes 200 or more people per event, focusing on women, nonbinary folk, and people of color. It originally began as a way to welcome lesbian women back to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Jordan described the takeovers of the straight bars—there are no lesbian bars left open in New Orleans— as a “tsunami of women.” While the events hold no formal connection to Southern Decadence, they aim to better represent the real population of New Orleans, something that the main celebration has seemingly failed to do.

“There really wasn’t any specific programming for women around Decadence, so we decided to do that. We all just combined forces and created this calendar of women’s events,” Jordan said. “In 2016, we had some magazines figure out we’re the largest indoor party of Southern Decadence, but the actual officials don’t really know that we exist,” she continued. “We don’t get any sponsorships or anything from Southern Decadence. We just decided to do it ourselves.”

GrrlSpot events are, in general, more organized and deliberate than Southern Decadence. Bars are generally alerted beforehand that the events will occur, and bathrooms are confirmed to be gender-neutral. Advertising is much more inclusive. Jordan tries to make sure that the GrrlSpot events around Decadence week get the most attention and “throws the kitchen sink at it, every time.”

Wherever the many people who decide to visit New Orleans this weekend choose where to spend their time and make the most of a city full of socialites, the true spirit of Southern Decadence lies in one phrase: “Change is inevitable,” Perez said. “All you can do is try and preserve that kernel of tradition that started the whole thing.”

Leave a comment